¶ 2Leave a comment on paragraph 2 0Wunderkammer. Pitzer College, Nichols Gallery at the Broad Center, Claremont, CA. January 24 – March 26, 2015. Curated by Ciara Ennis.

¶ 3Leave a comment on paragraph 3 0Cosmologies. First Street Gallery Art Center, Claremont, CA. January 24 – March 20, 2015. Curated by Ciara Ennis and Christopher Michno.

¶ 4Leave a comment on paragraph 4 0

Just exactly what is it that constitutes an archive? Although this may seem a transparently obvious question, the term has, in fact, been used to cover various theoretical constructs; to describe the structure and content of cultural memory; to identify sites for the operation of institutional power and the practice of interpretation; as well as to define and locate more prosaic processes and brick-and-mortar places, not to mention actual and virtual collections of documents and a multiplicity of other objects. Needless to say, the ongoing explosion of digital technologies has been marked by a concomitant globalization of archival activity and (at least for some) has raised the specter (or the hope) of a totalizing convergence of information and power in a singular and self-perpetuating meta-archive.2

¶ 5Leave a comment on paragraph 5 0

It is not at all clear, however, that this potential development is by any means inevitable. Writing as early as 1969 in The Archaeology of Knowledge, Michel Foucault argued that our own archive, despite comprising both “the law [of all the things that] can be said [and] the system that governs the appearance of statements as unique events,” is perforce always seen as incomplete, since it is viewed always and necessarily from the inside out.3 This apparent incompleteness has two important consequences. Not only does it open up a convenient space for interpretation,4 it also encourages the construction of alternative or counter-archives—vehicles for the collection, organization, and display of knowledge that can challenge the hegemonic and totalizing aspirations of “the archive in general.”5 Furthermore, this challenge effectively constitutes both an implicit description and an explicit critique of that general archive, disrupting our “temporal [language- and practice-bound] identities” and re-appropriating, at least in representation, the “discontinuities of history.”6

¶ 8Leave a comment on paragraph 8 0

The two shows under consideration here provide examples of how this critique can work in relation to the specific notion of an archive as a vehicle for the collection and display of knowledge conceived under the twin and intersecting rubrics of “science” and “art.” Although marked by significant differences (more on these below), when taken in toto the two exhibitions provide a powerful collection of fragments of externalized artistic and quasi-scientific cultural memory that challenge ingrained ways of seeing, organizing, and understanding the world.7 They are thus explicit excavations of the notion of the counter-archive.

¶ 9Leave a comment on paragraph 9 0

As curator Ciara Ennis makes plain, the general model around which the curatorial practice of the two exhibitions was organized is the early modern notion of the Kunst– or Wunderkammer, which functions as an “anachronistic” and “radical ‘other’ to the aesthetic regime of traditional museum display.”8 In Foucault’s terms, the use of this model instantiates a system of display that draws power from the fact that it “falls outside our [own] discursive practice.”9

¶ 10Leave a comment on paragraph 10 0

In institutional and conceptual terms, Wunderkammer was the centrally important of the two exhibitions since it foregrounded both works of art and curatorial practices that were consciously intended to “disrupt normative expectations about the function of contemporary exhibitions,” thereby “reinvigorating and radicalizing the contemporary museum apparatus.”10 Although Cosmologies also made use of unconventional or non-normative strategies of display (for example, the hanging of figurative work in minimalist grids or serial sequence), in general those strategies served to underline the “stylistic singularit[ies],”11 marvelously eccentric discursive practices, and world-making imaginations of a group of differently abled artists who would normally be marginalized (read: simply disregarded) under the “exclusionary and hierarchical value systems that [characterize] the current museological apparatus.”12

¶ 13Leave a comment on paragraph 13 0

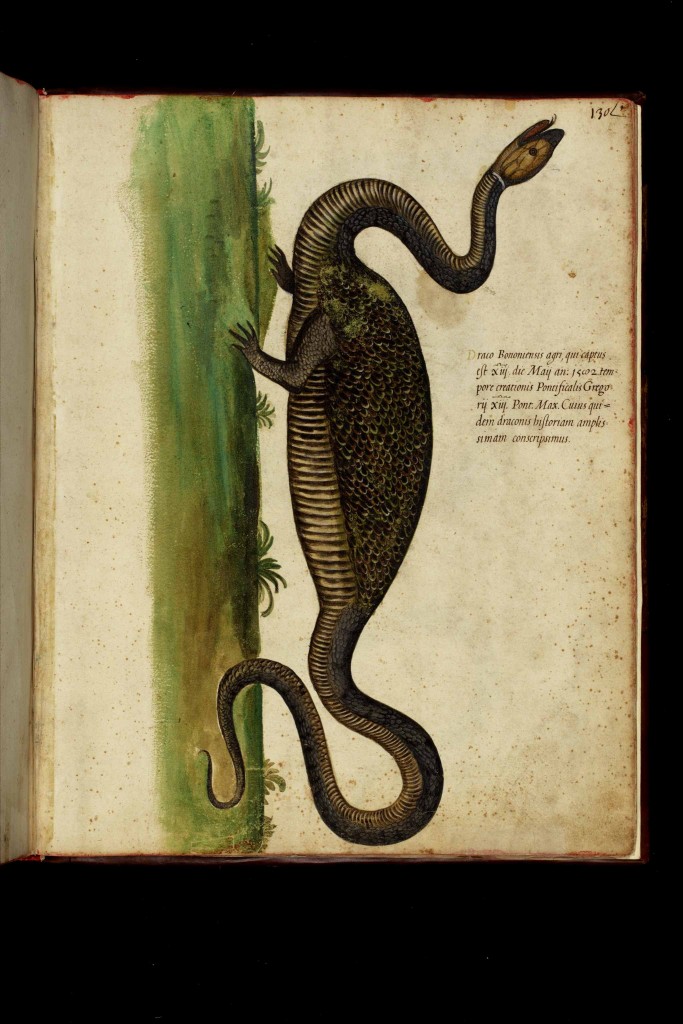

May 13, 1572: On the very day that a native son acceded to the Throne of Saint Peter as Pope Gregory XIII, a dragon was captured in the Bolognese hinterland.13 It was a monster, a marvel, and perhaps an ill omen, a portent of impending disaster. Fortunately, Bologna was also home to the papal nephew, Ulisse Aldrovandi, a brilliant naturalist, inveterate collector, prodigious author, and (thanks to his uncle’s elevation) resident at the scintillant center of humanist knowledge and papal power. In short, and to borrow a term from the provocative reflections in Jacque Derrida’s 1994 Mal d’archive, Aldrovandi was the perfect archon. His scientific and natural-historical preeminence, as well as his power as a gatekeeper of his own museum, ensured that the marvelous dragon would be appropriately examined, cataloged, interpreted, and, finally, archived both literally, as an exhibit in Aldrovandi’s comprehensive collection, and figuratively, within the corpus of late Renaissance natural knowledge.14

¶ 15Leave a comment on paragraph 15 0

Unfortunately, time has not been kind to Aldrovandi’s dragon. A slow but relentless process of “scientization” inevitably marginalized and eventually either reinterpreted or simply dismissed as non-existent the vast majority of prodigious creatures like the Bolognese dragon.15 The specimen itself, whatever its original identity, has been lost. And both the knowledge and the power that it embodied have been bracketed and filed in a dossier now archived under the heading, “Curiosities in the History of Early Modern Science.”

¶ 16Leave a comment on paragraph 16 0

What remains is a narrative of its travails (the history so trenchantly set down by Paula Findlen) and an image.16 Posed against a rather summary ground sparsely marked along its upper edge by scattered clumps of vegetation, we see the dragon standing in profile. A rather unlikely, if generally scaly and snake-like creature, the dragon has a bulbous body, a long, sinuous neck with more-or-less reptilian head (its mouth open as if in a defensive hiss), and a long, whip-like tail. Were it not for the two stubby legs—perhaps more properly “arms” since they clearly attach to the body, where one would imagine the shoulder girdle to be located—it might almost be possible to rationalize the creature as a snake who has just swallowed whole the most massive of all imaginable meals. There is no indication of size, although in that regard the creature seems anything but monstrous; but there is an inscription written out above the creature’s back. This text gives but scant information, noting the date of the find, its coincidence with the investiture of Gregory XIII, and promising an amplissimam (most ample and complete) discussion at some later date.17

¶ 17Leave a comment on paragraph 17 0

In terms of its fantastic and ferocious (if somewhat whimsical) appearance, as well as its concise juxtaposition of text and image, we might well pair Aldrovandi’s dragon with this contemporary work, which represents a creature that I have dubbed “the beast” by way of comparison.

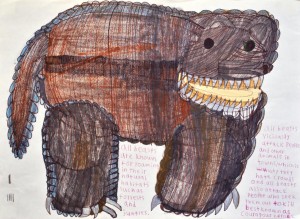

¶ 18Leave a comment on paragraph 18 0Figure 4. Evan Hynes, Animal of Gore (2014). 18×24”. Colored pencils and marker on paper. Photo: Seth Pringle.

¶ 19Leave a comment on paragraph 19 0

Evan Hynes’s Animal of Gore, a modestly sized drawing with text in colored pencils and marker on paper, was hung so as to form a kind of visual introduction to the Cosmologies exhibition. There could hardly have been a better choice. The beast itself is a kind of armored bear with ponderous elephantine legs and especially wicked-looking teeth and claws. Although floating free against an unmarked ground, the two blocks of text tucked in strategically make it quite clear that the beast itself (albeit a deadly “Animal of Gore”) is embedded in a complex narrative that comprises the artist’s own cosmology of the everyday imaginary:

¶ 20Leave a comment on paragraph 20 0all beasts are known for roaming in their natural habitats such as forests and jungles. all beasts viciously attack people and other animals in towns, which is why they hate crowds and all beasts also attack people who seek them out to kill best known as courageous heroes.

¶ 21Leave a comment on paragraph 21 0

Like all the First Street Gallery artists whose cosmologies were on show, Hynes has created a prolific and extremely imaginative body of interconnected work while facing developmental disabilities, a fact that might at first seem to guarantee a fatal marginalization, a too easy identification of his art-making with a kind of vacuous art therapy. And undoubtedly, Hynes’s practice, in common with the practice of all artists, I would argue, does have a deep therapeutic value insofar as it gives outward, physical form to a complex and insistent interiority.

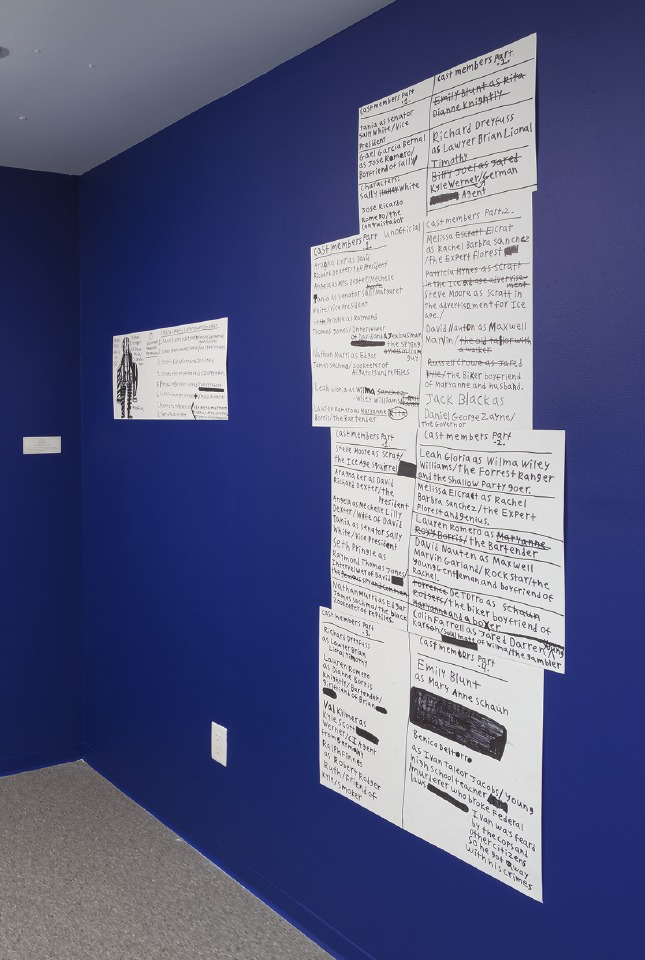

¶ 22Leave a comment on paragraph 22 0Figure 5. Right: Evan Hynes, Stories (2014). Dimensions variable. Marker on paper. Photo: Robert Weydemeyer.

¶ 23Leave a comment on paragraph 23 0

But precisely because he is, in more positive terms, differently abled, Hynes is capable of summoning forth a visual and textual world that is at once obviously contiguous with our world (the mundane one that he and I necessarily share) and yet strikingly discontinuous with it.18 His texts and images thus comprise exactly the kind of counter-archive alluded to above: one that challenges the dominant archival mode not only in terms of the content of the cultural memory that it externalizes, but also in the strategies that it deploys to articulate interpretations of that memory.19

¶ 24Leave a comment on paragraph 24 0

Interestingly enough, in its mode of presentation and juxtaposition of image and text, Animal of Gore bears a striking resemblance to Aldrovandi’s illustration of the marvelous and portentous dragon. Indeed, the resemblance is close enough that it is hard to avoid the conclusion that Aldrovandi’s archive might serve equally well the purpose that I have suggested for the bestial cosmology of Evan Hynes. But whereas Hynes’s Animal owes its power at least in part to the arbitrary contingencies of developmental genetics, the challenge that Aldrovandi’s dragon entails is its separation from the hegemonic archive across the gap of historical distance. And it is to the question of history and its distances that we now turn.

¶ 27Leave a comment on paragraph 27 0

As long as an archive remains nothing more than a collection of literal, figurative, or digital dossiers filed away in cabinets, warehouses, or servers, it remains essentially “a closed book.” It still retains a power to mold our collective cultural memory, but that power is exercised passively, through acts of concealment, effacement, and erasure.20 Although we know that the archive is perforce fragmentary, and that this necessary fragmentation makes its content available for interpretation, we cannot easily “get at” the fractures and ruptures that provide us with interpretive points of entry into its interior.21 In order for any archive to become really effective, it must be made manifest. It must become public through the operation of various technologies of revelation and display, of which the museum is certainly one of the most important, and most contested.

¶ 28Leave a comment on paragraph 28 0

Thus, if the Cosmologies exhibition challenged the normative or hegemonic archive through the proposition of alternative worlds of knowledge, personal visions, and interpretations that exist in parallel with or tangential to those that constitute the norm, Wunderkammer challenged the normative technologies of display that can govern our access to archival material. Since the overall strategy of the show, as indicated even by its name, suggests a process of defamiliarization through the invocation of historical distance (a return to the early modern world of the humanist Wunderkammer to which I have already alluded in my invocation of Aldrovandi), it is only proper that the collections and museums treated by the show as a whole, and by the work of individual artists, cover both art and natural history.22

¶ 29Leave a comment on paragraph 29 0

Among the most characteristic strategies of display in the “classic” natural history museum as it developed in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries is the exotic—quintessentially African—animal diorama, used to display mounted specimens in carefully constructed settings intended to evoke the actual environments in which they were “collected.”23 These dioramas can be quite meticulously constructed, in some cases attempting to re-present not just a generic environment but, for example, a quite specific location where particular lions were collected on the Serengetti Plain.24

¶ 30Leave a comment on paragraph 30 0Figure 6. Left: Clare Graham (Mor’York), Stuffed Hawk (n.d.). Right: Vivian Sming, ABSENCE (2011). Installation proposal. 10 5/8×7” framed. Photo: Robert Weydemeyer.

¶ 31Leave a comment on paragraph 31 0Wunderkammer, in a whole group of works, shows us what happens when this complex machinery is disassembled and its parts examined. We can begin with the thought experiment Vivian Sming suggested in her 2011 installation proposal, Absence, whose starkly framed text reads simply, “Remove all animals from natural history museum dioramas.” Aside from the pointed commentary on ecology and the politics of extinction (we are asked to imagine a world without lions, without zebras, without wildebeests, etc.),25 the work provides an equally pointed demonstration of the necessary relationship between an object (it might be a being, a text, an event, whatever) and the context that renders it potentially intelligible—that is, available for interpretation. Absent its object, context is necessarily empty of meaning, like an imaginary yet vacant Serengetti that we see lit up behind glass in a shadowy hall in a neo-classical building on Central Park West.26

¶ 32Leave a comment on paragraph 32 0

Conversely, a consciously decontextualized object, like Clare Graham’s Stuffed Hawk (n.d.), which might easily have been removed from one of those museum dioramas, also appears drained of meaning, alienated from any obvious semantic structure. I can identify the hawk as an immature red-tail (Buteo jamaicensis) but only by supplying a wholly other context, defined by my own experience as a birder and circumscribed by illustrated texts like The Sibley Field Guide to Birds of Western North America.27

¶ 33Leave a comment on paragraph 33 0Figure 7. Clare Graham (Mor’York), Vitrine (n.d.), detail. Dimensions and contents variable. Photo: Robert Weydemeyer.

¶ 34Leave a comment on paragraph 34 0

At the other end of the spectrum, the same artist’s complex installation, Vitrines (also n.d.),28 explicitly evokes the Renaissance Wunderkammer of the exhibition’s title. It brings together a diverse collection of objects (some simple, some complex; some natural, some man-made; some unworked, some finely crafted) according to a cryptic taxonomy that echoes the Kunstkammer’s originating distinction, naturalia-artificialia, but which at the same time references a world of idiosyncratic objects and processes.29 The individual objects—both natural and crafted—are often quite beautiful (and many are elegant in their refined simplicity), but since we have no immediate access to their governing cosmology, divining their possible relationships presents a complicated problem of interpretation. Indeed, although we have both an archive and an archon (the artist himself), we lack the shared cultural context, the agreed upon nexus of knowledge and power, that made Aldrovandi’s dragon legible and intelligible for his humanist peers. And then there are the mirrors.

¶ 36Leave a comment on paragraph 36 0

A number of small, portable mirrors have been strategically placed on the cases themselves. These function to expand the space of the piece in a number of interesting ways. First and in general, they suggest that the world encased in the vitrines, according to the figurative logic of synecdoche or part-for-whole, can in fact somehow transcend that confinement and reach out to enfold the entire exhibition, engulfing its differently figured worlds as the raw material for its own meta-archive.30 Second, certain reflections (for example those that capture the image of Joshua Callaghan’s Shields)31 draw our attention to other works that seem (perhaps) capable of aiding us in the project of interpretation—in this case, through both formal and conceptual correspondences. Finally, of course, the mirrors allow us to insert ourselves into the world of the work, while at the same time reminding us of our inevitable separation and distance from it. But these mirrored reflections do not simply mirror our physical presence in (front of) the work; they also figure the operation of interpretation itself as an informed and self-reflexive seeing that takes place both within and outside of its intended object.

¶ 37Leave a comment on paragraph 37 0

Perhaps this Wunderkammer’s most insidious challenge to the traditional scientific archive comes in a form that amounts essentially to (an annotated) counterfeit, a carefully crafted replica that is at least as much a product of self-reflexive art as it is a re-construction of the structure of taxonomic science. This is Jenny Yurshanky’s marvelously inventive Blacklisted: A Planted Allegory (Herbarium) (2015), which plays off the idea of the natural history archive precisely at that moment of transition from arbitrary concatenation of wonders and curiosities to repository of modern taxonomic systems.32

¶ 39Leave a comment on paragraph 39 0Figure 10. Jenny Yurshansky, Blacklisted: A Planted Allegory (Herbarium), detail of hand-cut silhouette. Photo: Jenny Yurshansky.

¶ 40Leave a comment on paragraph 40 0

At the heart of Blacklisted: A Planted Allegory is what appears to be a cabinet for the housing of pressed botanical specimens, of the type that can be most immediately associated with the taxonomic researches of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. And indeed, this cabinet does contain specimens of a sort: hand-crafted paper cut-outs of the pressed silhouettes of species of “invasive” or non-native plants collected on the campus of the Claremont Colleges in Claremont, CA.33 As a fabricated replica of a functioning piece of classical archival machinery, Blacklisted: A Planted Allegory (Herbarium) is an artistic tour-de-force. It is, however, also an allegory.

¶ 41Leave a comment on paragraph 41 0

In fact, it is an allegory that cuts two ways, both of which involve a meditation on the technical terms “invasive” and “non-native.” A bit of terminological context: a “non-native” plant is any plant found in a particular area that is not indigenous to that area. As a matter of convenience, the term is often applied to imported plants that serve an agricultural or decorative function, like the English roses in my front garden. “Invasive” plants, on the other hand, may or may not have been conscious imports and may or may not have been intended to perform a specific function (the numerous species of Eucalyptus trees that thrive in California at the expense of indigenous species are a good example). Whatever their origin, they are now considered simply “weeds,” out-of-control interlopers whose only “purpose” is the degradation of “native” eco-systems, and whose preferred fate is systematic extirpation.34

¶ 42Leave a comment on paragraph 42 0

Or, for “extirpation” substitute “deportation.” As a work generated in southern California, the political dimension that characterizes Blacklisted’s allegory is hard to avoid, and quite intentional.35 And since the artist, in fact, collaborated with the Pitzer College landscaping staff in collecting the plants for the project, it is easy to imagine “non-native” (even, some might say, “invasive”) workers helping to chronicle the degradation of the Claremont eco-system by their botanical analogs.

¶ 45Leave a comment on paragraph 45 0

It is, however, not always entirely clear what identifies a native or non-native species,36 or a non-native worker for that matter. Nor is it necessarily the case that the campus of the Claremont Colleges in fact constitutes an eco-system capable of invasive degradation. At least to a certain extent, the answers to these questions depend on a system for dividing up and grouping together objects on the basis of a system of similarities and differences—that is, on a system of classical taxonomy of the sort Michel Foucault described.37

¶ 46Leave a comment on paragraph 46 0

As a general rule, it is assumed that these taxonomic systems are necessarily arbitrary (that is, non-natural artifacts of culture); for example, the system derived by Linnaeus (1707-1778) for the classification of plants on the basis of the structure of their flowers assumes that homology of structure equals taxonomic association. The arrangement of the natural world of animals and plants was long held to comprise a special case (with a potentially legible and natural order) owing to the unique power of its originating myth.38 Ironically, that myth has lately acquired some scientific heft, owing to the insights of modern evolutionary and genetic science.39

¶ 47Leave a comment on paragraph 47 0

In the case of Jenny Yurshansky’s Blacklisted: A Planted Allegory (Herbarium), that tension between “natural” and “arbitrary” organizational designations is brought to the foreground in such a way that it allows us to see a radical challenge to fundamental ecological assumptions, while it also provokes a reflection on the history and politics of immigration and assimilation. Perhaps human intervention in previously natural eco-systems has now reached a point where the fundamental and defining distinction between “nature” (from which we as humans are perforce alienated by our very humanity) and “culture” (that anthropocentric world from which we can see nature as if across some unbridgeable gap) has broken down—we are a natural species after all—and there exists only the shell of a natural world now completely penetrated by cultural activity.40

¶ 48Leave a comment on paragraph 48 0

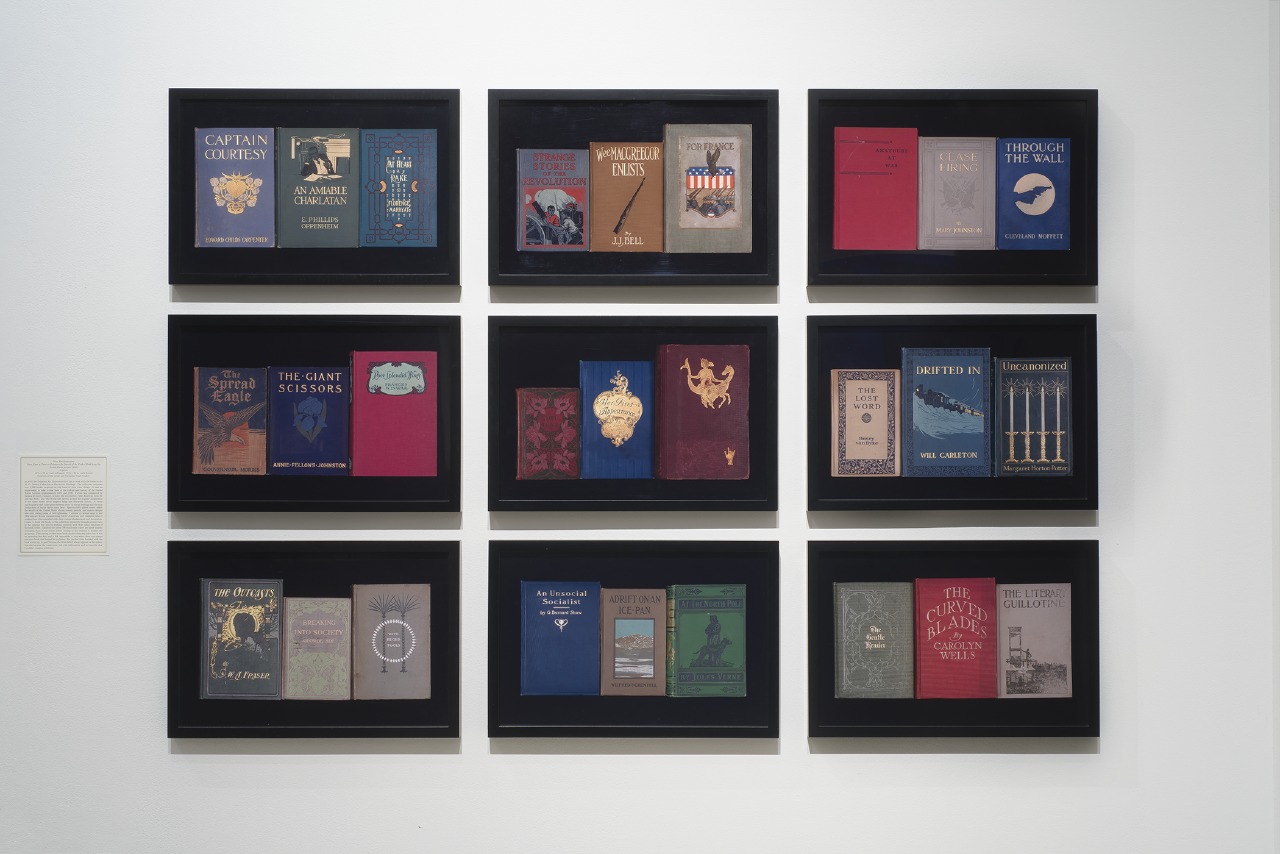

Although the depth and sweep of Yurshansky’s Blacklisted: A Planted Allegory is unique, both Cosmologies and Wunderkammer contain numerous works where artists (whether consciously or not) have leveraged the arbitrary nature of taxonomies into brilliantly crafted mini-archives, grouping and re-arranging everything from antique book covers41 to classes of people and cultural icons42 into gridded displays of framed images that simultaneously conceal intellectual and narrative connections and provide just enough information to encourage wide-ranging interpretation. On the one hand, these archival exercises are clearly personal, based on occulted or hidden taxonomies. On the other, they nevertheless draw on a shared cultural heritage that helps frame our own interpretations and provides material to stimulate our own taxonomic and archival activity.

¶ 50Leave a comment on paragraph 50 0Figure 11. Nina Katchadourian, Once Upon a Time in Delaware/In Search of the Perfect Book from the Sorted Books project (2012). Each image: 13 1/2×20” framed. C-Prints. Photo: Robert Weydemeyer.

¶ 53Leave a comment on paragraph 53 0

Not that we need much in the way of stimulation or encouragement. Indeed, it seems that we have all become compulsive archivists: masters of the iOS photo stream, of Facebook, and Instagram; of Google and Amazon, Netflix and YouTube; and countless other platforms, programs, devices, and interfaces—all deeply entangled in complex feedback loops that pass our thoughts and images, our information, our lives, our fears and desires, and our avatars through unnumbered technologies that mine and archive and remember and act on that information.

¶ 54Leave a comment on paragraph 54 0

In some ways, this is not a new situation. Ever since the original Whole Earth Catalog (1968-1972) promised us “Access to Tools,” and Mr. Natural reminded us to “Get the Right Tool for the Job” (his perennial advice to Flaky Foont—now a meme in its own right), the generation to which I belong has been more-or-less consciously involved in a series of struggles both over the control of the means of cultural production and the means to preserve the fruits of that production within our own collective and heterogeneous cultural archives.43 But with the advent of the digital revolution, the rules of engagement under which that struggle is waged have been altered profoundly.

¶ 55Leave a comment on paragraph 55 0

Although this is hardly the time to attempt a systematic dissection of that complex and at times self-contradictory cultural history, a brief examination of two final works in the Pitzer College Wunderkammer can certainly help to illuminate it in outline. The first, Michael Decker’s That’s Not The Way It Feels (2015) seems utterly removed from the phenomena I have just described. Mounted in a gallery stairwell, Decker’s piece comprises a collection of wooden wall plaques, of the sort generally associated with working- or lower-middle-class domestic interiors, the kind of thing you might find inside all those “little houses made of ticky-tacky” or the homey version of Robert Venturi’s decorated vernacular sheds.44

¶ 56Leave a comment on paragraph 56 0Figure 13. Michael Decker, That’s Not The Way It Feels (2015). Dimensions variable. Collection of Wooden Wall Plaques. LEFT Photo: author. RIGHT Photo: Robert Weydemeyer.

¶ 57Leave a comment on paragraph 57 0

This is a world of unapologetic kitsch: teddy bears and balloons; unicorns and wise, old owls; snails in shades and cute little girls in retro-bonnets, where “God is Love” and “Happiness is having you for a grandma.” It is also a world of memes and tag lines waiting to happen. It is a world that has been digitally replicated and globally disseminated, a world that connects scrapbooking and Facebooking, a world that I can enter instantly in any of its pop-cultural incarnations—all equally vacuous and, taken in toto, an incipient archive of almost infinite extent and apparently geological depth.

¶ 58Leave a comment on paragraph 58 0Figure 14. Rachel Mayeri, Life Cycle of Toxoplasma Gondii (2015). Twenty-nine-screen looped video installation. Photo: Robert Weydemeyer.

¶ 59Leave a comment on paragraph 59 0

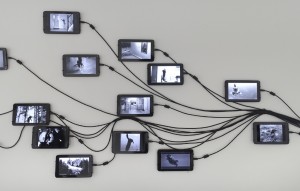

The second, Rachel Mayeri’s 2015 twenty-nine-screen looped video installation, Life Cycle of Toxoplasma Gondii, imagines an equally extensive digital world. In some ways, it is very close to Decker’s world (or at least one tiny kitty-cat corner of it) now explosively expanded, transmogrified, and internally disrupted by guerilla warfare. In order to make sense of the installation, a little epidemiological background is in order. Toxoplasma gondii is a single-celled parasite that can infect most any warm-blooded animal. However, it can only reproduce in cats, its essential reservoir host. It is transmitted via the relatively common oral-fecal route, and undoubtedly infects an enormous numbers of cat owners; anyone who has ever cleaned out a cat box, for example, is potentially at risk. For people with healthy immune systems, toxoplasmosis is generally asymptomatic. The parasites are held in check by the immune system, which also guards against subsequent re-infection. For infants (not really relevant here) and people with compromised immune systems (for example, people with HIV/AIDS, taking steroids, on chemotherapy, or otherwise immunosuppressed) the situation is quite different. In those cases, T. gondii can invade the eyes, potentially causing blindness, and the brain, where serious and irreversible damage can occur, including encephalitis, seizures, and death.

¶ 60Leave a comment on paragraph 60 0

Keeping all this in mind, the subversive intent of Mayeri’s appropriated kitty videos now becomes clear. The first group provides a humorous recapitulation of the oral-fecal circulation of the parasite through a particular cat-infested environment: in this case, YouTube, although Facebook would do just as well. Alas, the medium itself is corrupt, riddled with some kind of inherent vice that provokes a suppression of the immune system in its habitual users (although T. gondii is not a virus, the notion of the viral video is surely in play here), with predictably and tragically demented results. These are recorded in the second set of clips, which can only be described as “extreme cat videos.” Cats dropped from a height to test their four-foot-landing reflex, cats bouncing off walls, cats strapped into drones, etc.45 Taken together, and “homogenized” in re-presentation into a black-and-white format that gives them all the look of the now increasingly ubiquitous cctv footage, these short videos, played again and again and again across a wide expanse of wall,46 are hypnotic. Given half a chance, they figuratively become the universally digitized world in all its vast extent and flickering shallowness.

¶ 61Leave a comment on paragraph 61 0

Like Jenny Yurshansky’s Blacklisted: A Planted Allegory (Herbarium), Rachel Mayeri’s Life Cycle of Toxoplasma Gondii has a clearly allegorical function. Indeed, both works turn the taxonomic and archival strategies of classical natural history and medical science back upon themselves to great effect. This is not simply a matter of unmasking the deep structure of representational systems that the centers of institutional power have naturalized within the dominant culture. Those very systems of representation have been seized and re-purposed, transformed into fragmentary counter-archives, collections of re-figured images and alternative interpretations that speak with one voice, if in a multitude of tongues.47

¶ 62Leave a comment on paragraph 62 0

In the studiolo of the Renaissance humanist, it was confidently imagined that the structure of the world was such that it could, in theory or in representation, be shut up in a single closet48 or enclosed within a single room—the fabulous Wunderkammer. We now know that this is not in fact the case, and that the parallel or overlapping physical universes posited by string theory, and other equally arcane cosmological speculations, exist already in the individual and counter-institutional cosmologies that proliferate within a viral and constantly mutating epistemology. The closet and the Kammer have become a screen, a keyboard, and a warehouse full of servers housing not physical specimens, but endless lines of code. What we want now is perhaps not so much a fixed and classical taxonomy as a flexible post-modern epidemiology. What we want now is not a way of fixing structure, but a way of tracking aetiology and mutational change. For we live today in a kind of digital Hot Zone, a world where the unified memory trace that we externalize as the hegemonic archive is constantly overwritten by numberless individual and communal traces. And each and every one of those represents a potential viral outbreak and an emergent counter-archive.

I realize that my choice of title here has a lengthy pedigree, stretching from Saint Matthew to T.S. Eliot via Lancelot Andrewes, and then on to Homi K. Bhabha and others. In simplest terms, my own intention in effecting yet one more appropriation is merely to propose a juxtaposition between the idea of the post-structuralist sign (as something given arbitrarily within a specific culture) and those natural wonders that resist the arbitrariness of modern systems of signification. However, it may be worth suggesting in the present context a possible connection between Eliot’s poetic formulation in “Gerontion” (1920) and Prof. Bhabha’s analysis in “Signs Taken for Wonders: Ambivalence and Authority under a Tree outside Delhi, May 1817,” Critical Inquiry 12, no. 1 (1985): 144-65. Whereas Eliot’s Gerontion, “an old man [living] in a dry month,” can only testify to the impacted impotence of “[t]he word within a word, unable to speak a word,” Bhabha sees in the same dead text the potential nascence of a post-colonial discourse, a mode of resistance born of repetition and re-appropriation. The structure of Prof. Bhabha’s argument has implications far beyond post-colonial theory: for example, for the structure of this essay. For a concrete post-colonial example drawing on the visual arts, see my article, “Continental Drift,” X-TRA Contemporary Art Quarterly 17, no. 3 (Spring 2015): 54-58, a review of the show Earth Matters: Land as Material and Metaphor in the Art of Africa at the UCLA Fowler Museum, particularly in my discussion of the work of Sammy Baloji. [↩]

To a certain extent, this is still a science-fiction conceit, although recent revelations about meta-data collection and mining by the National Security Agency and others have given it a frightening immediacy. [↩]

Michel Foucault, “The Historical a priori and the Archive,” excerpted from The Archaeology of Knowledge in Charles Merewether, The Archive (London and Cambridge, MA: Whitechapel/MIT, 2006), 28. Although the argument is not quite so explicit, the same conclusion can be drawn if the moment of the archive’s initial theorization is taken to be Freud’s 1925 essay “A Note upon the Mystic Writing Pad.” See my article, “Some Notes on the Archive,” X-TRA Contemporary Art Quarterly 14, no. 3 (Spring 2012): 14-25, http://x-traonline.org/article/some-notes-on-the-archive/, which provides the basic theoretical framework for this essay. [↩]

It is precisely at points of fracture and discontinuity in an image, a text, or an archive that interpretation can, as it were, gain a foothold. [↩]

Ibid. In the present case, the use of the idea and the image of the Wunderkammer, which seeks to privilege an anachronistic archival system and, in fact, to use it as a lens to reflect back on more contemporary systems, is clearly akin to the ideas Mieke Bal puts forward, in a somewhat different context, in her notion of “preposterous history.” Mieke Bal, Quoting Caravaggio: Contemporary Art, Preposterous History (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999). Her answer (4-5) to the question “Who illuminates whom?” provides a concise definition of her term. [↩]

For a wonderful work that appropriates the structure of the Kunst- or Wunderkammer in a way that specifically evokes Prof. Bhabha’s analysis (n.1), see Amalia Mesa-Bains’ New World Wunderkammer, an installation at the UCLA Fowler Museum, October 13, 2013-January 26, 2014. [↩]

Ciara Ennis, personal communication, August 7, 2015. In addition, I should thank Ciara Ennis, as well as her First Street Gallery co-curator Christopher Michno, the artist Jenny Yurshanski, and my good friend Debra Cashion for their conversation and written comments regarding the exhibitions, their own work, and the argument developed in my text. [↩]

Foucault, The Archive, 30. At this point in his text, Foucault seems to equate “that which falls outside our [own] discursive practice” with “what we can no longer say.” It seems clear that “what we can no longer say” must entail some implicit qualification, for example, “within the parameters of that discursive practice.” Thus, the evocation of the Wunderkammer in this context must be seen as, in effect, a quotation or as a representation. [↩]

The narrative of the Bolognese dragon, its discovery, and subsequent “domestication” by Ulisse Aldrovandi appears in Paula Findlen, Possessing Nature: Museums, Collecting, and Scientific Culture in Early Modern Italy (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994), 17-31. [↩]

For the notion of the archon as one who speaks with a power of command invested by the state, see Jacques Derrida, Archive Fever (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996 [1994]), 2. See also Carolyn Steedman, Dust: The Archive and Cultural History (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2002), 1-16. [↩]

Findlen, Possessing Nature, 19, Fig. 1, gives the original manuscript illustration wings, and a more ferocious and “dragon-like” appearance characterized the creature in the illustration prepared for the eventual, posthumous publication. [↩]

The “Serpent Book,” Serpentium et draconum historiae libri duo, was finally published posthumously in Bologna in 1639. Findlen, Possessing Nature, 25, n. 26. [↩]

The relationship between the culture(s) of the “differently abled” and those of us who are seen simply as “abled” has become a vast and complex set of overlapping fields of inquiry. Enormous amounts of useful material has been collected in works like Lennard J. Davis, The Disability Studies Reader, 4th ed. (New York and Oxford: Routledge, 2013); in the present context, see (as a representative and useful example), Joseph N. Straus, “Autism as Culture,” in The Disability Studies Reader, 460-84. [↩]

Hynes is one of a number of First Street artists whose work also appears in the Wunderkammer exhibition. There, the cosmos represented by “the beast” is expanded and enriched in his 2014 marker on paper text installation, Stories. Likewise, Joe Zaldivar’s City and Regional Maps of 2012-14 (colored pencils, markers, pen, pencil, and watercolor on paper) both recapitulates in enormously painstaking detail a whole vanishing universe of illustrated fold-out maps (which he meticulously copies free-hand) and stands over and against the high-tech geographical archive provided by Google Earth, for example. [↩]

The penultimate scene in Steven Spielberg’s 1981 film, Raiders of the Lost Ark, when the crate holding the Ark of the Covenant is wheeled into the space of an enormous warehouse, bulging with other crated treasures, is the paradigmatic image here. The occult and scientific power of the Nazis was no match for the Ark’s; but the bureaucratic archons of the U.S. government were able to efface its existence with no trouble. [↩]

If the terms Kunst- and Wunderkammer evoke notions of art (and craft[smanship]) as well as the idea of the marvelous, the English term “Cabinet of Curiosities” evokes yet another category, that of “the curious,” as a descriptor. Stephen Bann has skillfully exploited this point of entry to construct an analytical frame for a certain class of artworks that he sees as exemplary of particular tendencies within postmodernity. See Stephen Bann, Ways around Modernism (London and New York: Routledge, 2007), 103-72. For a discussion of the most famous institutional instantiation of the notion of the curious as a systematic organizing principle, see Lawrence Weschler, Mr. Wilson’s Cabinet of Wonder (New York: Pantheon, 1995). [↩]

In this instance, of course, “collected” is synonymous with “killed.” Whether or not the elision of the reference to death is conscious, the verb “collect” is used as a covering term for the acquisition of museum specimens, whether they are animals, fossils, minerals, or works of art. Even as an adult, I find natural history dioramas of this sort immediately compelling, and the cool dark halls where they are often installed more resonant with “religious” associations than is the case, for example, in art museums, the traditional “temples” of High Culture. For the amazing history of three of America’s most well-known dioramas (lion installations in Pittsburg, New York, and Chicago) see Rachel Poliquin, The Breathless Zoo: Taxidermy and the Cultures of Longing (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2012), 96-101. [↩]

This is true of the American Museum of Natural History group in New York. Ibid., 98. [↩]

While ecological speculation usually posits that in a world where lions are extinct, the only lions extant will be those collected in museums, Sming’s Absence seems rather to suggest that we imagine the diorama as a stand-in for the world of Nature at large: no lions “in Nature,” no lions to collect for the museum diorama. [↩]

On the other hand, if the lions remain present, the hall, the building, the Park, and the city (even the world) are all potentially entailed in their interpretive context. [↩]

The exhibition, in this case Wunderkammer itself, can also provide a context, albeit one that radically alters the potential meaning of the specimen. [↩]

Rather than simply rejecting the “vitrine culture” so characteristic of contemporary museum display, the artist seeks to subvert it (see installation photo) through his disruption of the spatial relations that typically characterize its use. For a similar defamiliarization of the iconic vitrine, see Stephen Bann’s discussion of Copenhagen’s Museum Gustavianum, in his Ways around Modernism, 130-32. [↩]

Porcelain, for example, seems to be an important material in the artist’s world, as are the simple yet mysterious little devices that once served to moisten the glue on the back of postage stamps or packing tape. [↩]

This also mirrors the strategy of the exhibition as a whole, which was planned both to disrupt the traditional “sixty inches off the floor” installation paradigm (conversation with Ciara Ennis, March 19, 2015) and to stimulate conversation between works that constitute diverse imaginary or alternative epistemologies. [↩]

Joshua Callaghan, Crow Shield (2011: wheel cover, crow feathers, leather, synthetic fleece, hemp twin, oil paint) and White Mountain Shield (2011: wheel cover, pigeon feathers, leather, hemp twine, oil paint). Clare Graham’s Vitrines contain a number of authentic anthropological specimens (for example, necklaces and other decorative objects from Papua, New Guinea) that play off nicely against the artifacts of Callaghan’s imaginary anthropology, opening up a whole array of questions centering around colonialism, the “exotic,” and the “primitive.” [↩]

The work was developed during Yurshansky’s tenure as a Pitzer College Artist in Residence (2014-15). That fragment of the entire work that was exhibited in the Wunderkammer exhibition appeared under the title Blacklisted: A Planted Allegory (Herbarium). [↩]

My friend Debra Cashion has raised the issue of the status of the artist’s craft, especially with respect to the cut-out “specimens” crafted for this work, which function as replacements for the original organic specimens rather than as illustrations or representations of them. This question is important in view of the epistemologically problematic status of “pictures” in relation to the structure of early modern science in general. Unfortunately, I cannot unpack this entire argument today. For an authoritative survey of the basic issues, see Sachiko Kusukawa, Picturing the Book of Nature: Image, Text, and Argument in Sixteenth-Century Anatomy and Medical Botany (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012). [↩]

We usually think of “weeds” as opportunistic plants, often non-native, and relentless invaders of gardens, lawns, and roadsides. From an ecological perspective, however, it is lifestyle and reproductive strategy that define “weediness,” and the term can be as easily applied to animals as plants. Although it is concerned with marine rather than terrestrial eco-systems, see Lisa-ann Gershwin, Stung! On Jellyfish Blooms and the Future of the Ocean (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013), 80-83, for a concise discussion of this issue. Following out this line of reasoning, it is easy to identify Homo sapiens as a prototypical weed, and to characterize our species as the world’s most disastrously “invasive” life form. For a survey of the most recent thinking, see Curtis W. Marean, “The Most Invasive Species of All,” Scientific American 313, no. 2 (August 2015): 32-9, with citations to relevant technical literature. [↩]

Conversations with Ciara Ennis and Jenny Yurshansky, March 6 and 26, 2015. [↩]

The horse is the paradigmatic example of this paradox. The ancestors of the horse evolved in North America approximately 55 million years ago. The group underwent a significant evolutionary radiation and spread through a number of woodland and plains habitats, adapting to the vagaries of climate change and eventually spreading south as well as west into Asia and Europe. With the passage of time, however, the group’s diversity declined (it is now represented by the single genus Equus), and about 10,000 years ago, horses went entirely extinct across North and South America. An important indigenous group had vanished, only to be re-introduced as a “non-native” in historical times. Its subsequent impact on the culture of the Plains Indians, and on eco-systems across the continent, was enormous. [↩]

This argument is developed in extenso in Michel Foucault, The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences (New York: Vintage, 1973). [↩]

Adam’s naming of the animals (Gen. 2:18-20) is the locus classicus for the idea that taxonomies were at least potentially capable of revealing natural rather than culturally determined systems of relationships between things. [↩]

The systematic technology in play here is that of cladistics, the plotting of phylogenetic relationships on the basis of shared derived characteristics. For a quite legible introduction, see the “Journey into Phylogenetic Systematics” at http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/clad/clad4.html, also with citations to more technical literature and a link to a wonderful kids’ module: “What did T. rex Taste Like?” (Answer: chicken.), http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/education/explorations/tours/Trex/index.html. [↩]

The literature on the putative “death of nature” is vast, and the problem has been approached from any number of perspectives. Just as a practical matter, or as an artifact of reading the newspaper, it must appear obvious, with even a little reflection, that the ubiquity of human activity and human presence have left literally nowhere on Earth unmarked. This situation is often discussed and theorized under the blanket term Anthropocene. For one example among many, see Timothy Morton, Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology after the End of the World (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013). The actual adoption of Anthropocene as a legitimate scientific term falls under the purview of the International Commission on Stratigraphy. See the website for an ongoing discussion on the Anthropocene, with extensive links to relevant publications and communications: Subcommission on Quaternary Stratigraphy, quaternary.stratigraphy.org, last updated on August 4, 2015. [↩]

See, among the works in Wunderkammer, Nina Katchadourian, Once Upon a Time in Delaware/In Search of the Perfect Book from the Sorted Books project (2012: C-prints, 12 ½ x 19,” each unframed). [↩]

Katchadourian’s 3×3 grid of framed book-cover triptychs can be matched with John Bayer’s taxonomy of human types and cultural icons (c. 2000: colored pencils, markers, and art sticks on paper), displayed in the Cosmologies exhibition. [↩]

Obviously, this struggle is hardly unique to my generation. The examples cited are intended simply to provide some chronological and cultural context. [↩]

“Little houses made of ticky-tacky” derives from the lyrics to Malvina Reynolds’ classic 1962 song, “Little Boxes,” bemoaning suburban conformity, and made famous by Pete Seeger’s 1963 cover. The idea of the “decorated shed” is central to Robert Venturi’s seminal post-modern theory of “ugly and boring architecture.” See Robert Venturi, Denise Scott Brown, and Steven Izenour, Learning from Las Vegas (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1977 [1972]), especially Part II, 85ff, for the elaboration of the theory in extenso. Figs. 140 and 142-44 are particularly relevant in the present context. [↩]

I recently discovered on Facebook an extraordinary if fragmentary music video entitled “Death Metal Cat,” which fits perfectly into this virulent category. Needless to say, I dutifully added my two views to the two million plus already recorded. [↩]

In the Wunderkammer exhibition, the piece was installed along a narrow balcony, forcing the viewer close enough so that it could easily encompass his or her entire visual field. [↩]

As at the moment of Pentecost; see Acts 2:1-13. [↩]

The well-known tag “A World of Wonders in one closet shut” is the final line of a quatrain used in the epitaph of the English collector John Tradescant (c. 1577-1638) and quoted in full, for example, in Findlen, Possessing Nature, 17, n. 1. [↩]

Signs Taken for Wonders

November 2015

¶ 1 Leave a comment on paragraph 1 0 Signs Taken for Wonders1

¶ 4 Leave a comment on paragraph 4 0 Just exactly what is it that constitutes an archive? Although this may seem a transparently obvious question, the term has, in fact, been used to cover various theoretical constructs; to describe the structure and content of cultural memory; to identify sites for the operation of institutional power and the practice of interpretation; as well as to define and locate more prosaic processes and brick-and-mortar places, not to mention actual and virtual collections of documents and a multiplicity of other objects. Needless to say, the ongoing explosion of digital technologies has been marked by a concomitant globalization of archival activity and (at least for some) has raised the specter (or the hope) of a totalizing convergence of information and power in a singular and self-perpetuating meta-archive.2

¶ 5 Leave a comment on paragraph 5 0 It is not at all clear, however, that this potential development is by any means inevitable. Writing as early as 1969 in The Archaeology of Knowledge, Michel Foucault argued that our own archive, despite comprising both “the law [of all the things that] can be said [and] the system that governs the appearance of statements as unique events,” is perforce always seen as incomplete, since it is viewed always and necessarily from the inside out.3 This apparent incompleteness has two important consequences. Not only does it open up a convenient space for interpretation,4 it also encourages the construction of alternative or counter-archives—vehicles for the collection, organization, and display of knowledge that can challenge the hegemonic and totalizing aspirations of “the archive in general.”5 Furthermore, this challenge effectively constitutes both an implicit description and an explicit critique of that general archive, disrupting our “temporal [language- and practice-bound] identities” and re-appropriating, at least in representation, the “discontinuities of history.”6

¶ 6 Leave a comment on paragraph 6 0 Figure 1. Wunderkammer: Installation view. Photo: Robert Weydemeyer.

Figure 1. Wunderkammer: Installation view. Photo: Robert Weydemeyer.

¶ 7 Leave a comment on paragraph 7 0 Figure 2. Cosmologies: Installation view. Photo: Christopher Michno.

Figure 2. Cosmologies: Installation view. Photo: Christopher Michno.

¶ 8 Leave a comment on paragraph 8 0 The two shows under consideration here provide examples of how this critique can work in relation to the specific notion of an archive as a vehicle for the collection and display of knowledge conceived under the twin and intersecting rubrics of “science” and “art.” Although marked by significant differences (more on these below), when taken in toto the two exhibitions provide a powerful collection of fragments of externalized artistic and quasi-scientific cultural memory that challenge ingrained ways of seeing, organizing, and understanding the world.7 They are thus explicit excavations of the notion of the counter-archive.

¶ 9 Leave a comment on paragraph 9 0 As curator Ciara Ennis makes plain, the general model around which the curatorial practice of the two exhibitions was organized is the early modern notion of the Kunst– or Wunderkammer, which functions as an “anachronistic” and “radical ‘other’ to the aesthetic regime of traditional museum display.”8 In Foucault’s terms, the use of this model instantiates a system of display that draws power from the fact that it “falls outside our [own] discursive practice.”9

¶ 10 Leave a comment on paragraph 10 0 In institutional and conceptual terms, Wunderkammer was the centrally important of the two exhibitions since it foregrounded both works of art and curatorial practices that were consciously intended to “disrupt normative expectations about the function of contemporary exhibitions,” thereby “reinvigorating and radicalizing the contemporary museum apparatus.”10 Although Cosmologies also made use of unconventional or non-normative strategies of display (for example, the hanging of figurative work in minimalist grids or serial sequence), in general those strategies served to underline the “stylistic singularit[ies],”11 marvelously eccentric discursive practices, and world-making imaginations of a group of differently abled artists who would normally be marginalized (read: simply disregarded) under the “exclusionary and hierarchical value systems that [characterize] the current museological apparatus.”12

¶ 11 Leave a comment on paragraph 11 0

¶ 12 Leave a comment on paragraph 12 0 The Dragon and the Beast: A Parable

¶ 13 Leave a comment on paragraph 13 0 May 13, 1572: On the very day that a native son acceded to the Throne of Saint Peter as Pope Gregory XIII, a dragon was captured in the Bolognese hinterland.13 It was a monster, a marvel, and perhaps an ill omen, a portent of impending disaster. Fortunately, Bologna was also home to the papal nephew, Ulisse Aldrovandi, a brilliant naturalist, inveterate collector, prodigious author, and (thanks to his uncle’s elevation) resident at the scintillant center of humanist knowledge and papal power. In short, and to borrow a term from the provocative reflections in Jacque Derrida’s 1994 Mal d’archive, Aldrovandi was the perfect archon. His scientific and natural-historical preeminence, as well as his power as a gatekeeper of his own museum, ensured that the marvelous dragon would be appropriately examined, cataloged, interpreted, and, finally, archived both literally, as an exhibit in Aldrovandi’s comprehensive collection, and figuratively, within the corpus of late Renaissance natural knowledge.14

¶ 14 Leave a comment on paragraph 14 0 Figure 3. Aldrovandi’s dragon.

Figure 3. Aldrovandi’s dragon.

Ulisse Aldrovandi, Tavole di animali, tomo IV, c. 130, Draco Bononiensis agri, Biblioteca Universitaria di Bologna.

© Biblioteca Universitaria di Bologna. Image used by permission.

http://www.filosofia.unibo.it/aldrovandi/pinakesweb/imagebrowse.asp?showframe=True&fileid=2264&compid=3425&complabel=Volume+composto+da+141+figure+di+pesci%2C+molluschi+…&shelfmark=Tavole+vol.+004+Animali

¶ 15 Leave a comment on paragraph 15 0 Unfortunately, time has not been kind to Aldrovandi’s dragon. A slow but relentless process of “scientization” inevitably marginalized and eventually either reinterpreted or simply dismissed as non-existent the vast majority of prodigious creatures like the Bolognese dragon.15 The specimen itself, whatever its original identity, has been lost. And both the knowledge and the power that it embodied have been bracketed and filed in a dossier now archived under the heading, “Curiosities in the History of Early Modern Science.”

¶ 16 Leave a comment on paragraph 16 0 What remains is a narrative of its travails (the history so trenchantly set down by Paula Findlen) and an image.16 Posed against a rather summary ground sparsely marked along its upper edge by scattered clumps of vegetation, we see the dragon standing in profile. A rather unlikely, if generally scaly and snake-like creature, the dragon has a bulbous body, a long, sinuous neck with more-or-less reptilian head (its mouth open as if in a defensive hiss), and a long, whip-like tail. Were it not for the two stubby legs—perhaps more properly “arms” since they clearly attach to the body, where one would imagine the shoulder girdle to be located—it might almost be possible to rationalize the creature as a snake who has just swallowed whole the most massive of all imaginable meals. There is no indication of size, although in that regard the creature seems anything but monstrous; but there is an inscription written out above the creature’s back. This text gives but scant information, noting the date of the find, its coincidence with the investiture of Gregory XIII, and promising an amplissimam (most ample and complete) discussion at some later date.17

¶ 17 Leave a comment on paragraph 17 0 In terms of its fantastic and ferocious (if somewhat whimsical) appearance, as well as its concise juxtaposition of text and image, we might well pair Aldrovandi’s dragon with this contemporary work, which represents a creature that I have dubbed “the beast” by way of comparison.

¶ 18 Leave a comment on paragraph 18 0 Figure 4. Evan Hynes, Animal of Gore (2014). 18×24”. Colored pencils and marker on paper. Photo: Seth Pringle.

Figure 4. Evan Hynes, Animal of Gore (2014). 18×24”. Colored pencils and marker on paper. Photo: Seth Pringle.

¶ 19 Leave a comment on paragraph 19 0 Evan Hynes’s Animal of Gore, a modestly sized drawing with text in colored pencils and marker on paper, was hung so as to form a kind of visual introduction to the Cosmologies exhibition. There could hardly have been a better choice. The beast itself is a kind of armored bear with ponderous elephantine legs and especially wicked-looking teeth and claws. Although floating free against an unmarked ground, the two blocks of text tucked in strategically make it quite clear that the beast itself (albeit a deadly “Animal of Gore”) is embedded in a complex narrative that comprises the artist’s own cosmology of the everyday imaginary:

¶ 21 Leave a comment on paragraph 21 0 Like all the First Street Gallery artists whose cosmologies were on show, Hynes has created a prolific and extremely imaginative body of interconnected work while facing developmental disabilities, a fact that might at first seem to guarantee a fatal marginalization, a too easy identification of his art-making with a kind of vacuous art therapy. And undoubtedly, Hynes’s practice, in common with the practice of all artists, I would argue, does have a deep therapeutic value insofar as it gives outward, physical form to a complex and insistent interiority.

¶ 22 Leave a comment on paragraph 22 0 Figure 5. Right: Evan Hynes, Stories (2014). Dimensions variable. Marker on paper. Photo: Robert Weydemeyer.

Figure 5. Right: Evan Hynes, Stories (2014). Dimensions variable. Marker on paper. Photo: Robert Weydemeyer.

¶ 23 Leave a comment on paragraph 23 0 But precisely because he is, in more positive terms, differently abled, Hynes is capable of summoning forth a visual and textual world that is at once obviously contiguous with our world (the mundane one that he and I necessarily share) and yet strikingly discontinuous with it.18 His texts and images thus comprise exactly the kind of counter-archive alluded to above: one that challenges the dominant archival mode not only in terms of the content of the cultural memory that it externalizes, but also in the strategies that it deploys to articulate interpretations of that memory.19

¶ 24 Leave a comment on paragraph 24 0 Interestingly enough, in its mode of presentation and juxtaposition of image and text, Animal of Gore bears a striking resemblance to Aldrovandi’s illustration of the marvelous and portentous dragon. Indeed, the resemblance is close enough that it is hard to avoid the conclusion that Aldrovandi’s archive might serve equally well the purpose that I have suggested for the bestial cosmology of Evan Hynes. But whereas Hynes’s Animal owes its power at least in part to the arbitrary contingencies of developmental genetics, the challenge that Aldrovandi’s dragon entails is its separation from the hegemonic archive across the gap of historical distance. And it is to the question of history and its distances that we now turn.

¶ 25 Leave a comment on paragraph 25 0

¶ 26 Leave a comment on paragraph 26 0 Technologies of Display

¶ 27 Leave a comment on paragraph 27 0 As long as an archive remains nothing more than a collection of literal, figurative, or digital dossiers filed away in cabinets, warehouses, or servers, it remains essentially “a closed book.” It still retains a power to mold our collective cultural memory, but that power is exercised passively, through acts of concealment, effacement, and erasure.20 Although we know that the archive is perforce fragmentary, and that this necessary fragmentation makes its content available for interpretation, we cannot easily “get at” the fractures and ruptures that provide us with interpretive points of entry into its interior.21 In order for any archive to become really effective, it must be made manifest. It must become public through the operation of various technologies of revelation and display, of which the museum is certainly one of the most important, and most contested.

¶ 28 Leave a comment on paragraph 28 0 Thus, if the Cosmologies exhibition challenged the normative or hegemonic archive through the proposition of alternative worlds of knowledge, personal visions, and interpretations that exist in parallel with or tangential to those that constitute the norm, Wunderkammer challenged the normative technologies of display that can govern our access to archival material. Since the overall strategy of the show, as indicated even by its name, suggests a process of defamiliarization through the invocation of historical distance (a return to the early modern world of the humanist Wunderkammer to which I have already alluded in my invocation of Aldrovandi), it is only proper that the collections and museums treated by the show as a whole, and by the work of individual artists, cover both art and natural history.22

¶ 29 Leave a comment on paragraph 29 0 Among the most characteristic strategies of display in the “classic” natural history museum as it developed in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries is the exotic—quintessentially African—animal diorama, used to display mounted specimens in carefully constructed settings intended to evoke the actual environments in which they were “collected.”23 These dioramas can be quite meticulously constructed, in some cases attempting to re-present not just a generic environment but, for example, a quite specific location where particular lions were collected on the Serengetti Plain.24

¶ 30 Leave a comment on paragraph 30 0 Figure 6. Left: Clare Graham (Mor’York), Stuffed Hawk (n.d.). Right: Vivian Sming, ABSENCE (2011). Installation proposal. 10 5/8×7” framed. Photo: Robert Weydemeyer.

Figure 6. Left: Clare Graham (Mor’York), Stuffed Hawk (n.d.). Right: Vivian Sming, ABSENCE (2011). Installation proposal. 10 5/8×7” framed. Photo: Robert Weydemeyer.

¶ 31 Leave a comment on paragraph 31 0 Wunderkammer, in a whole group of works, shows us what happens when this complex machinery is disassembled and its parts examined. We can begin with the thought experiment Vivian Sming suggested in her 2011 installation proposal, Absence, whose starkly framed text reads simply, “Remove all animals from natural history museum dioramas.” Aside from the pointed commentary on ecology and the politics of extinction (we are asked to imagine a world without lions, without zebras, without wildebeests, etc.),25 the work provides an equally pointed demonstration of the necessary relationship between an object (it might be a being, a text, an event, whatever) and the context that renders it potentially intelligible—that is, available for interpretation. Absent its object, context is necessarily empty of meaning, like an imaginary yet vacant Serengetti that we see lit up behind glass in a shadowy hall in a neo-classical building on Central Park West.26

¶ 32 Leave a comment on paragraph 32 0 Conversely, a consciously decontextualized object, like Clare Graham’s Stuffed Hawk (n.d.), which might easily have been removed from one of those museum dioramas, also appears drained of meaning, alienated from any obvious semantic structure. I can identify the hawk as an immature red-tail (Buteo jamaicensis) but only by supplying a wholly other context, defined by my own experience as a birder and circumscribed by illustrated texts like The Sibley Field Guide to Birds of Western North America.27

¶ 33 Leave a comment on paragraph 33 0 Figure 7. Clare Graham (Mor’York), Vitrine (n.d.), detail. Dimensions and contents variable. Photo: Robert Weydemeyer.

Figure 7. Clare Graham (Mor’York), Vitrine (n.d.), detail. Dimensions and contents variable. Photo: Robert Weydemeyer.

¶ 34 Leave a comment on paragraph 34 0 At the other end of the spectrum, the same artist’s complex installation, Vitrines (also n.d.),28 explicitly evokes the Renaissance Wunderkammer of the exhibition’s title. It brings together a diverse collection of objects (some simple, some complex; some natural, some man-made; some unworked, some finely crafted) according to a cryptic taxonomy that echoes the Kunstkammer’s originating distinction, naturalia-artificialia, but which at the same time references a world of idiosyncratic objects and processes.29 The individual objects—both natural and crafted—are often quite beautiful (and many are elegant in their refined simplicity), but since we have no immediate access to their governing cosmology, divining their possible relationships presents a complicated problem of interpretation. Indeed, although we have both an archive and an archon (the artist himself), we lack the shared cultural context, the agreed upon nexus of knowledge and power, that made Aldrovandi’s dragon legible and intelligible for his humanist peers. And then there are the mirrors.

¶ 35 Leave a comment on paragraph 35 0 Figure 8. Clare Graham (Mor’York), Vitrine (n.d.), detail. Photo: author.

Figure 8. Clare Graham (Mor’York), Vitrine (n.d.), detail. Photo: author.

¶ 36 Leave a comment on paragraph 36 0 A number of small, portable mirrors have been strategically placed on the cases themselves. These function to expand the space of the piece in a number of interesting ways. First and in general, they suggest that the world encased in the vitrines, according to the figurative logic of synecdoche or part-for-whole, can in fact somehow transcend that confinement and reach out to enfold the entire exhibition, engulfing its differently figured worlds as the raw material for its own meta-archive.30 Second, certain reflections (for example those that capture the image of Joshua Callaghan’s Shields)31 draw our attention to other works that seem (perhaps) capable of aiding us in the project of interpretation—in this case, through both formal and conceptual correspondences. Finally, of course, the mirrors allow us to insert ourselves into the world of the work, while at the same time reminding us of our inevitable separation and distance from it. But these mirrored reflections do not simply mirror our physical presence in (front of) the work; they also figure the operation of interpretation itself as an informed and self-reflexive seeing that takes place both within and outside of its intended object.

¶ 37 Leave a comment on paragraph 37 0 Perhaps this Wunderkammer’s most insidious challenge to the traditional scientific archive comes in a form that amounts essentially to (an annotated) counterfeit, a carefully crafted replica that is at least as much a product of self-reflexive art as it is a re-construction of the structure of taxonomic science. This is Jenny Yurshanky’s marvelously inventive Blacklisted: A Planted Allegory (Herbarium) (2015), which plays off the idea of the natural history archive precisely at that moment of transition from arbitrary concatenation of wonders and curiosities to repository of modern taxonomic systems.32

¶ 38 Leave a comment on paragraph 38 0 Figure 9. Jenny Yurshansky, Blacklisted: A Planted Allegory (Herbarium) (2015). 25x20x122.” Steel herbarium cabinets, MDF, wood, brass, assorted paper, 133 hand-cut silhouettes. Photo: Jenny Yurshansky.

Figure 9. Jenny Yurshansky, Blacklisted: A Planted Allegory (Herbarium) (2015). 25x20x122.” Steel herbarium cabinets, MDF, wood, brass, assorted paper, 133 hand-cut silhouettes. Photo: Jenny Yurshansky.

¶ 39 Leave a comment on paragraph 39 0 Figure 10. Jenny Yurshansky, Blacklisted: A Planted Allegory (Herbarium), detail of hand-cut silhouette. Photo: Jenny Yurshansky.

Figure 10. Jenny Yurshansky, Blacklisted: A Planted Allegory (Herbarium), detail of hand-cut silhouette. Photo: Jenny Yurshansky.

¶ 40 Leave a comment on paragraph 40 0 At the heart of Blacklisted: A Planted Allegory is what appears to be a cabinet for the housing of pressed botanical specimens, of the type that can be most immediately associated with the taxonomic researches of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. And indeed, this cabinet does contain specimens of a sort: hand-crafted paper cut-outs of the pressed silhouettes of species of “invasive” or non-native plants collected on the campus of the Claremont Colleges in Claremont, CA.33 As a fabricated replica of a functioning piece of classical archival machinery, Blacklisted: A Planted Allegory (Herbarium) is an artistic tour-de-force. It is, however, also an allegory.

¶ 41 Leave a comment on paragraph 41 0 In fact, it is an allegory that cuts two ways, both of which involve a meditation on the technical terms “invasive” and “non-native.” A bit of terminological context: a “non-native” plant is any plant found in a particular area that is not indigenous to that area. As a matter of convenience, the term is often applied to imported plants that serve an agricultural or decorative function, like the English roses in my front garden. “Invasive” plants, on the other hand, may or may not have been conscious imports and may or may not have been intended to perform a specific function (the numerous species of Eucalyptus trees that thrive in California at the expense of indigenous species are a good example). Whatever their origin, they are now considered simply “weeds,” out-of-control interlopers whose only “purpose” is the degradation of “native” eco-systems, and whose preferred fate is systematic extirpation.34

¶ 42 Leave a comment on paragraph 42 0 Or, for “extirpation” substitute “deportation.” As a work generated in southern California, the political dimension that characterizes Blacklisted’s allegory is hard to avoid, and quite intentional.35 And since the artist, in fact, collaborated with the Pitzer College landscaping staff in collecting the plants for the project, it is easy to imagine “non-native” (even, some might say, “invasive”) workers helping to chronicle the degradation of the Claremont eco-system by their botanical analogs.

¶ 43 Leave a comment on paragraph 43 0

¶ 44 Leave a comment on paragraph 44 0 Taxonomy

¶ 45 Leave a comment on paragraph 45 0 It is, however, not always entirely clear what identifies a native or non-native species,36 or a non-native worker for that matter. Nor is it necessarily the case that the campus of the Claremont Colleges in fact constitutes an eco-system capable of invasive degradation. At least to a certain extent, the answers to these questions depend on a system for dividing up and grouping together objects on the basis of a system of similarities and differences—that is, on a system of classical taxonomy of the sort Michel Foucault described.37

¶ 46 Leave a comment on paragraph 46 0 As a general rule, it is assumed that these taxonomic systems are necessarily arbitrary (that is, non-natural artifacts of culture); for example, the system derived by Linnaeus (1707-1778) for the classification of plants on the basis of the structure of their flowers assumes that homology of structure equals taxonomic association. The arrangement of the natural world of animals and plants was long held to comprise a special case (with a potentially legible and natural order) owing to the unique power of its originating myth.38 Ironically, that myth has lately acquired some scientific heft, owing to the insights of modern evolutionary and genetic science.39

¶ 47 Leave a comment on paragraph 47 0 In the case of Jenny Yurshansky’s Blacklisted: A Planted Allegory (Herbarium), that tension between “natural” and “arbitrary” organizational designations is brought to the foreground in such a way that it allows us to see a radical challenge to fundamental ecological assumptions, while it also provokes a reflection on the history and politics of immigration and assimilation. Perhaps human intervention in previously natural eco-systems has now reached a point where the fundamental and defining distinction between “nature” (from which we as humans are perforce alienated by our very humanity) and “culture” (that anthropocentric world from which we can see nature as if across some unbridgeable gap) has broken down—we are a natural species after all—and there exists only the shell of a natural world now completely penetrated by cultural activity.40

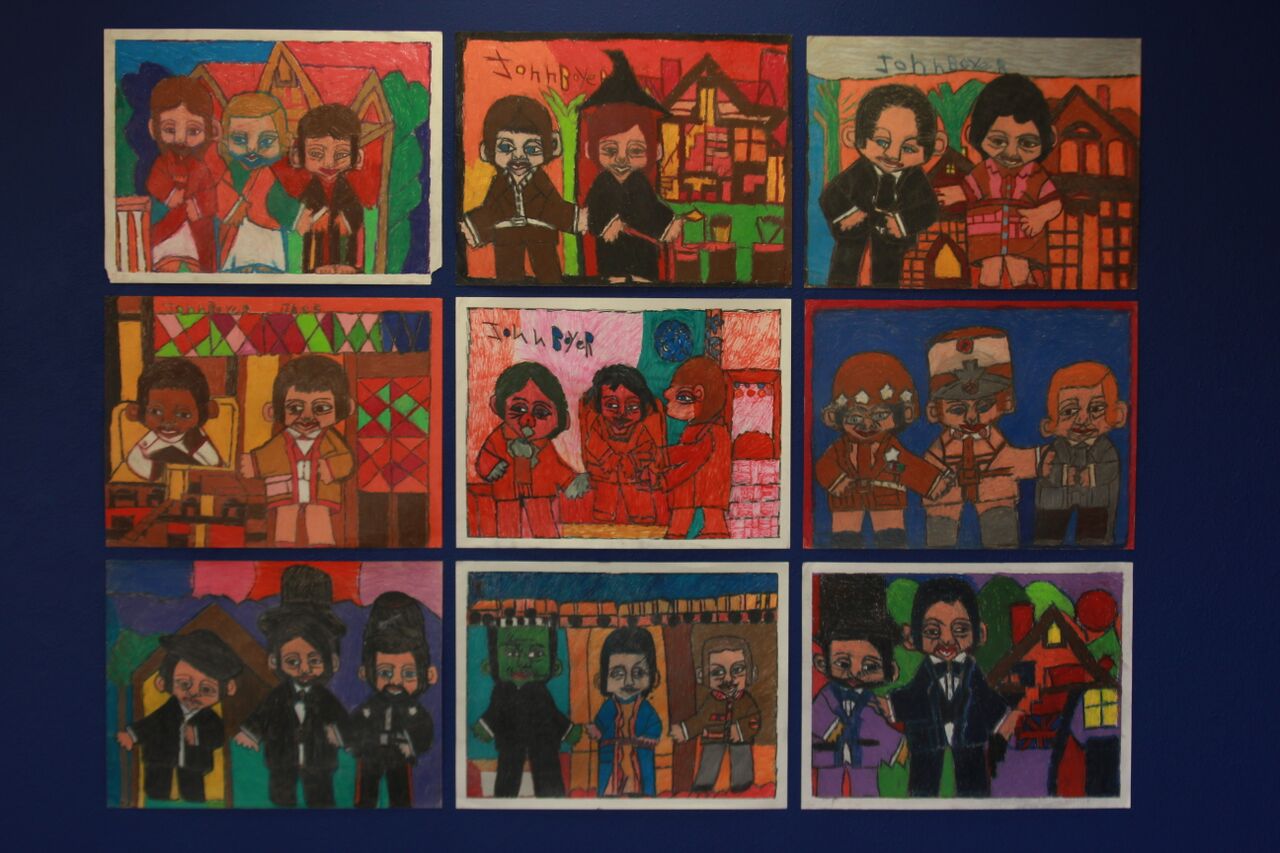

¶ 48 Leave a comment on paragraph 48 0 Although the depth and sweep of Yurshansky’s Blacklisted: A Planted Allegory is unique, both Cosmologies and Wunderkammer contain numerous works where artists (whether consciously or not) have leveraged the arbitrary nature of taxonomies into brilliantly crafted mini-archives, grouping and re-arranging everything from antique book covers41 to classes of people and cultural icons42 into gridded displays of framed images that simultaneously conceal intellectual and narrative connections and provide just enough information to encourage wide-ranging interpretation. On the one hand, these archival exercises are clearly personal, based on occulted or hidden taxonomies. On the other, they nevertheless draw on a shared cultural heritage that helps frame our own interpretations and provides material to stimulate our own taxonomic and archival activity.

¶ 49 Leave a comment on paragraph 49 0

¶ 50 Leave a comment on paragraph 50 0 Figure 11. Nina Katchadourian, Once Upon a Time in Delaware/In Search of the Perfect Book from the Sorted Books project (2012). Each image: 13 1/2×20” framed. C-Prints. Photo: Robert Weydemeyer.

Figure 11. Nina Katchadourian, Once Upon a Time in Delaware/In Search of the Perfect Book from the Sorted Books project (2012). Each image: 13 1/2×20” framed. C-Prints. Photo: Robert Weydemeyer.

¶ 51 Leave a comment on paragraph 51 0 Figure 12. John Bayer, 9 x Untitled (c.2000). Art sticks on paper. Photo: Christopher Michno.

Figure 12. John Bayer, 9 x Untitled (c.2000). Art sticks on paper. Photo: Christopher Michno.

¶ 52 Leave a comment on paragraph 52 0 Wired—Killer Cat Videos

¶ 53 Leave a comment on paragraph 53 0 Not that we need much in the way of stimulation or encouragement. Indeed, it seems that we have all become compulsive archivists: masters of the iOS photo stream, of Facebook, and Instagram; of Google and Amazon, Netflix and YouTube; and countless other platforms, programs, devices, and interfaces—all deeply entangled in complex feedback loops that pass our thoughts and images, our information, our lives, our fears and desires, and our avatars through unnumbered technologies that mine and archive and remember and act on that information.

¶ 54 Leave a comment on paragraph 54 0 In some ways, this is not a new situation. Ever since the original Whole Earth Catalog (1968-1972) promised us “Access to Tools,” and Mr. Natural reminded us to “Get the Right Tool for the Job” (his perennial advice to Flaky Foont—now a meme in its own right), the generation to which I belong has been more-or-less consciously involved in a series of struggles both over the control of the means of cultural production and the means to preserve the fruits of that production within our own collective and heterogeneous cultural archives.43 But with the advent of the digital revolution, the rules of engagement under which that struggle is waged have been altered profoundly.

¶ 55 Leave a comment on paragraph 55 0 Although this is hardly the time to attempt a systematic dissection of that complex and at times self-contradictory cultural history, a brief examination of two final works in the Pitzer College Wunderkammer can certainly help to illuminate it in outline. The first, Michael Decker’s That’s Not The Way It Feels (2015) seems utterly removed from the phenomena I have just described. Mounted in a gallery stairwell, Decker’s piece comprises a collection of wooden wall plaques, of the sort generally associated with working- or lower-middle-class domestic interiors, the kind of thing you might find inside all those “little houses made of ticky-tacky” or the homey version of Robert Venturi’s decorated vernacular sheds.44

¶ 56 Leave a comment on paragraph 56 0 Figure 13. Michael Decker, That’s Not The Way It Feels (2015). Dimensions variable. Collection of Wooden Wall Plaques.

Figure 13. Michael Decker, That’s Not The Way It Feels (2015). Dimensions variable. Collection of Wooden Wall Plaques.

LEFT Photo: author. RIGHT Photo: Robert Weydemeyer.

¶ 57 Leave a comment on paragraph 57 0 This is a world of unapologetic kitsch: teddy bears and balloons; unicorns and wise, old owls; snails in shades and cute little girls in retro-bonnets, where “God is Love” and “Happiness is having you for a grandma.” It is also a world of memes and tag lines waiting to happen. It is a world that has been digitally replicated and globally disseminated, a world that connects scrapbooking and Facebooking, a world that I can enter instantly in any of its pop-cultural incarnations—all equally vacuous and, taken in toto, an incipient archive of almost infinite extent and apparently geological depth.

¶ 58 Leave a comment on paragraph 58 0 Figure 14. Rachel Mayeri, Life Cycle of Toxoplasma Gondii (2015). Twenty-nine-screen looped video installation. Photo: Robert Weydemeyer.

Figure 14. Rachel Mayeri, Life Cycle of Toxoplasma Gondii (2015). Twenty-nine-screen looped video installation. Photo: Robert Weydemeyer.